The hike up to the peak of Cima Dome is not long from the off-road trail that runs along the side of Tuetonia Peak but it is misleading. I parked my FJ Cruiser in a small campground turnout and looked up at the smooth arc of the Dome’s volcanic bulge and thought “That’s not far.”

Somehow, in the years spent making photographs in the Mojave National Preserve, first as part of a national park residency in 2019 when I spent four weeks exploring and photographing all corners of the Preserve to now, in the Spring of 2023, nearing the end of an intense multi-year project documenting the historic fire in the Joshua tree forest, I had never climbed to the top of Cima Dome.

The fire was in August of 2020, the result of the Armageddon-like “lightning siege” that struck all over California, starting fires that destroyed towns and shocked the nation. All the news coverage was focused on the populated areas, of course, but way out here in the middle of the desert, way out here where the ecosystem was unfamiliar with fire and not at all adapted to it, a forest fire raged, burning sixty-four square miles, burning out the center of what was the largest and densest Joshua tree forest in the world.

On my first visit there, not long after the fire, the ground, once dense with small plant life, was bare to the sand, ghostly ash shadows airbrushed on the ground everywhere. Then, over the next months, over the next years, there was growth, there was life, wildflowers and scattered weeds, and finally thickly growing grasses that probably don’t belong at all, perhaps ready to spread the next fire.

But the trees didn’t grow. The dead trees were blackened from the fire and the charred bark fell off in patches revealing a startling white surface underneath, the work of a fungus. With every trip, subject to the relentless desert winds, I saw more trees that had fallen over. Well over one million trees were burned, they say, and I suspect none of them will be left standing in the end.

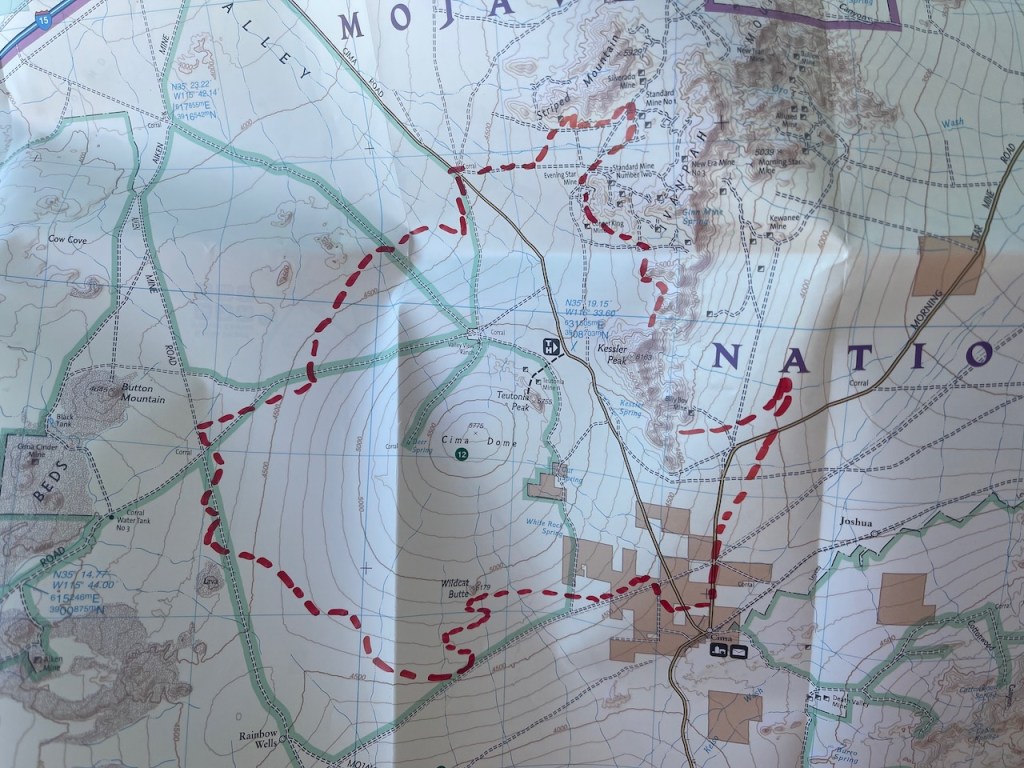

Climbing up the Dome is climbing into the heart of the fire, the most impossible-to-save part, away from roads and the ranch and historic structures that were a priority of the limited firefighting resources. It was only a little ways straight up to the top from where I left the FJ but the curved line of the Dome you could see from the little campsite wasn’t the curve of the Dome at all but rather the curve of the first wave of land, the first fold of the Earth, the first of many. Like the photo project itself, I’d again and again think I saw the top, the finish line, so to speak, and again and again another wave appeared before me. Up and down, up and down, all the way to the top.

I don’t know how many trips I have made to this black and white forest, how many cumulative weeks and months. I thought about purchasing a little house hereabouts, and seriously contemplated buying an RV, just to park it at a campsite across from the Tuetonia Peak trailhead. My wife commented a few months ago that if I died I should be cremated and my ashes scattered upon the Dome. She assumed I was in full agreement, not so much suggesting the idea as confirming the obvious.

After the hike I dozed off a bit, sitting in the driver’s seat, miles from anyone, and awoke as the sun was setting, Kessler Peak alive and salmon-colored in the last seconds of the day. And then I was standing on a ridge looking toward the New York Mountains, the rising Moon behind filling the valley with its eternal light, the dead trees spread out before me no longer aware of day and night, and I felt for the first time that I was done.