(This review is co-published with Photobook Journal: The Contemporary Photobook Magazine.)

When I was a young man I labored through the book On Photography, by Susan Sontag. I was a subscriber to the New York Review of Books, though not during the early 1970s when the chapters in this book were initially published as separate essays. I was also a subscriber to MIT’s art magazine October, which, like the NYRB, was aimed at liberal intellectuals. Despite this early and persistent contact it took me a long while to recognize the full truth of Barnett Newman’s oft-repeated quip “Aesthetics is to artists what ornithology is to birds.”

David Campany, currently based at the International Center of Photography in New York, is an ornithologist of this sort. He specializes in photography and his prodigious output on the topic is remarkable.

His newest book, On Photographs, takes its title from Sontag’s and, as Campany relates in his introduction, from a meeting he had with her in which he raised concerns that prompted Sontag to ask “What is it about my writings on photography that worry you?” The title of his (future) book was suggested by Sontag herself as a reply to those concerns.

When I read On Photography back when I was, oh, twenty years old I had concerns of my own.

Every few months my quarterly issue of October would come in (along with all of the other art magazines I subscribed to or purchased on the newsstand) and I would slog through its pages trying to decipher what the heck they were talking about. Oh, yes, Marx was there on every page it seemed–and Freud, too. Art intellectuals of that time loved Marx and Freud. There was lots of talk about deconstruction and about French theorists and printed in that journal were some of the most convoluted, impenetrable sentences ever written in earnest. And when you took a deep look, when you really boiled it down, you would often find that that jargon-filled article was saying, at its very heart, nothing much at all.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: It is impossible to pull off a Sokal Hoax in the art world—impossible because the whole thing is already like a Sokal Hoax.

On Photography offered me that same sort of experience. Bits here and there were interesting, some of it seemed contradictory or even wrong, some of it I didn’t at all understand, but the overriding sense of things was that whatever Sontag was talking about when she used the word “photography” it wasn’t the same “photography” that I was experiencing. Not that I disagreed with her so much as thought her work irrelevant to mine, despite the claims of so many that it was so crucial.

Ornithologists and birds, again.

When I bought Campany’s book I knew almost nothing about it, aside from the title and its pointed reference to Sontag’s, his title suggesting to me that I should expect a refutation of her work—she talking about something called “photography,” he talking about actual photographs—or possibly an augmentation of her work, he supplying the photographic flesh to her wordy bones.

I was steeled for Sontag, in whichever direction it would go, but what I got when I opened the cover of On Photographs was John Szarkowski.

Szarkowski was and remains the most influential photography curator thus far in the history of photography. He shaped the crucial growing-up period of the medium as a curator at the Museum of Modern Art from the early 1970s to his retirement in 1991. He is the only curator mentioned anywhere in Sontag’s On Photography and she mentions him only twice, both times in a chapter originally published in 1977. Here’s the more substantive mention:

While in principle all subjects are worthy pretexts for exercising the photographic way of seeing, the convention has arisen that photographic seeing is clearest in offbeat or trivial subject matter. Subjects are chosen because they are boring or banal. Because we are indifferent to them, they best show up the ability of the camera to “see.” When Irving Penn, known for his handsome photographs of celebrities and food for fashion magazines and ad agencies, was given a show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1975, it was for a series of close-ups of cigarette butts. “One might guess,” commented the director of the museum’s Department of Photography, John Szarkowski, “that [Penn] has only rarely enjoyed more than a cursory interest in the nominal interest of his pictures.” Writing about another photographer, Szarkowski commends what can “be coaxed from subject matter” that is “proudly banal.”

And this I just the sort of thing that drives me nuts about Sontag’s sort of writing—and hers is a high-quality example of the genre. Yes, photographers will sometimes photograph things like cigarette butts or porcelain toilets or cloud-covered skies where the subject, a priori, seems banal. But is banality the point?

It’s true that Penn’s MOMA show was all cigarette butts—fourteen large platinum prints, lovingly printed. They must have been beautiful to behold. That’s a point Sontag left out. Here is Gene Thorton, reviewing this same show in the New York Times in 1975, offering a similar quote from Szarkowski:

So why is he photographing cigarette butts? According to the exhibition wall label written by John Szarkowski, director of the Modern’s photography department, Mr. Penn is not photographing cigarette butts at all: he is making works of art. “The capricious and frankly inconsequential nature of the nominal subject matter, in conjunction with its ambitious and enormously sophisticated handling, constitute a clear statement of intention: these photographs can be considered only as works of art.” What Mr. Szarkowski means by this is that in a work of art, the subject matter is not important; only the treatment is. Mr. Penn could have achieved the same effect with any subject matter.

Well, we have heard that before. As infants at the knees of our art appreciation teachers, we have all learned that Cezanne’s apples are greater than Raphael’s madonnas; that treatment, not subject matter, makes the difference. But I propose a test. I propose imagining that would happen if Mr. Penn had lavished his considerable artistry on pictures of roses rather than dirty cigarette butts. I guess that the viewer would murmur, “How pretty,” and then go on to the next gallery. It is precisely the contrast between Mr. Penn’s impeccable technique and his revolting subject matter that grabs the viewer’s attention and makes him linger a moment longer, torn by an incredulity he, does not wish to confess, even to himself. With roses, Mr. Penn would have made only pretty pictures, no matter how ambitious and sophisticated his handling. With cigarette butts, he has made minor masterpieces of modern art. So subject matter is important after all.

Yes, that’s it, or at least part of it. A photograph isn’t just subject matter and, in fact, subject matter may not even be the most important factor in a photograph’s power. Sometimes subject matter is important in unexpected ways, sometimes even intertwining with the materials and methods used to produce the image.

This is obvious to the birds who fly through photography’s winds and perch on its trees. Maybe not so obvious to the ornithologist who sits in her office, field guides open on her desk.

It was obvious to John Szarkowski who, despite Sontag’s caricature, curated all sorts of shows, not just platinum prints of banal cigarette butts. Looking at the whole of his writings and the breadth of the exhibitions he curated he seemed far more attuned to the broad possibilities of photography and his approach I sense was to look at a photograph first and to see what it offered. Less polemical (and maybe, therefore, less exciting to academics) but more useful and honest.

That’s a nice idea—to look at a photograph, to really look at it, and to see where looking at it will lead you. You might even imagine looking intently and thoughtfully at a photograph and then to write up a short essay, a sort of exploration of both the photograph itself and your reflection upon it and the wider field of photography.

And that is exactly what Szarkowski did with his 1973 Looking at Photographs, a landmark publication and still an excellent way for those interested in photography as an art form to be introduced not so much to facts and figures about each of the one hundred photographs featured on its pages but to be introduced to a way of thinking about photographs, a way of seeing photographs where the word used in that particular way is always italicized.

Arranged in very rough chronological order, the book covers the main thrust of art photography (as the very idea itself formed) up to the 1960s or so. That’s a lot of ground to cover and Szarkowski does so with gentle confidence and often poetry, sharing an image from William Shew at the beginning of the book (“The picture should be looked at with its case not fully opened, preferably in private and by lamplight, as one would approach a secret.”) to a Paul Strand mushroom photograph somewhere in the middle of the book (“When the great wild continent had been finally conquered, Strand rediscovered the rhythms of the wilderness in microcosm.”) to the last image, a landscape with utility pole by Henry Wessel, Jr. (“It is today quite simple to make pictures that are as intelligent, cultivated, and original as the person who makes them—who remains, of course, the most interesting and undependable link in the system.”).

Irving Penn is there but not his cigarette butts. His photograph, Woman in a Black Dress, is just that, and Szarkowski is, appropriately, talking about subject matter again:

The true subject of the photograph is the sinuous, vermicular, richly subtle line that describes the silhouetted shape. The line has little to do with women’s bodies or real dresses, but rather with an ideal of efflorescent elegance to which certain exceptional women and their couturiers once aspired.

He’s not really nailing it in any of these essays, of course. The photograph remains the photograph in each case—if what the photograph had to offer could be contained in a paragraph or two or three, even a paragraph or two or three by Szarkowski, then why show the photograph at all? But he’s exploring the works, feeling his way through them.

Looking At Photographs is a nice book and better yet a nice format. Essay and photo, essay and photo, all the way to the end.

Much to my surprise that is what I found in On Photographs, not something directly about On Photography so much as a sort of update to Szarkowski’s work, with Sontag mentioned only twice (listed only once in the index but see pages 11 and 168). This isn’t to say she isn’t there, mixed in below the surface of the text and perhaps learnedly considered when selecting the images. Campany is an intellectual and as such Sontag’s work—a seminal effort in the history of the analysis of photography from a social-science-y point of view—will always be there, somewhere.

And as an intellectual, Campany’s concerns often drift to the nature of photography and the deeper meta-meanings of it all—yes, Walter Benjamin makes his appearances, and so does Roland Barthes, and many of the theorist wack-a-moles of university English departments that pop in and out. To Campany’s great credit I don’t recall seeing any mention of Foucault or Derrida, omissions that, along with the election of Joe Biden as president and the successful development of COVID vaccines, give me hope for our future. He does use the word “colonialism,” just once, however, as seemingly required by contract nowadays.

But here I am doing just that which I said not to do a few paragraphs ago, bringing to a work, in this case a book, all sorts of other stuff before I even crack the cover. I’ve got it all backward. I need to clear my head and look at the book, to really look at it, really read it, and to see where looking and reading will lead me.

Its one hundred and nineteen photographs and one hundred and nineteen one-page essays are bound together by the MIT Press, and though it looks disturbingly like one of the anthologies of October both in its size and with its white cover and black and red text, On Photographs is much more inviting if you open to a page at random.

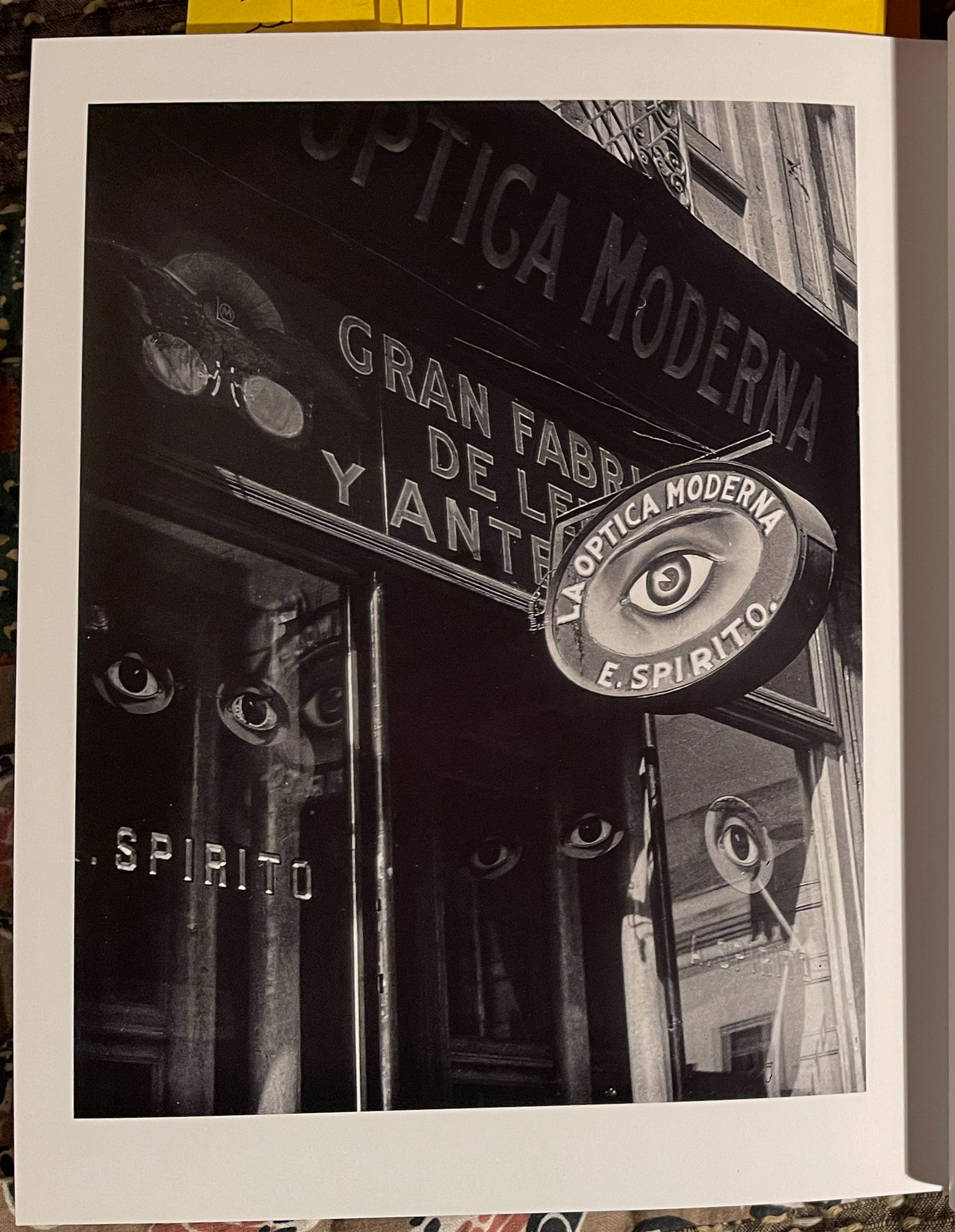

Take the Manuel Alvarez Bravo image of an optometrist shop window with freaky eyes painted not only upon the sign but disembodied alone and in pairs on the various windows. It’s surrealism-time already when Bravio picked the shutter but then, as Campany relates, at the last minute before the photograph was published, Bravo chose to keep the orientation of the image which had been accidentally reversed by the printer. Backward, the words on the sign and windows disappear from legibility and become a pretend language, no longer grabbing your eye like actual words tend to do, the letters becoming photographic again.

Soon after we come to a William Eggleston image, an older woman glaring at the viewer in front of a wall painted all the colors of the rainbow, fragmented into a randomly sorted grid. In his essay Campany, straightfaced, quotes Eggleston:

…I was entranced by what [that woman] was wearing—her sweater and dress, light red and white—and how the color of her lips and fingernails went beautifully with those colors. The wall—those multicolors—is just incidental.

and you are dumbfounded by the audacity of Eggleston’s bullshit. He was an artist in more ways than one!

Turn the page and there is the famous Ruth Orkin image, the young woman quickly walking down some Italian street, walking the daily gauntlet. It is lined with men of all ages and each of them is staring at her and reacting to her, some quietly spying on her beauty, others catcalling their invitations.

Campany has dug up the issue of Cosmopolitan in which this image first appeared and offers this unintentionally sinister excerpt from the accompanying article:

Solo voyaging need hold no terrors for the feminine tourist. It’s fun, it’s easy, and it’s the best way in the world to meet new people—men, for instance. Having no-one but yourself to depend on and being away from friends who expect you always to be yourself, you are likely to develop a brand-new self-reliance and charm. Besides, two girls or a group traveling together look like a closed corporation, and are less likely to join other people’s fun.

Creepy creepy or perhaps the darkest of dark comedies? Campany reminds us that

Once it is out in the world, a photograph can acquire meaning well beyond intention. And if a photograph becomes “iconic,” as this one has, it is not because it carries some universal meaning; rather, it is open to different interpretations.

Indeed, and “beyond” is exactly the right word here, suggesting that of all the reasonable interpretations the original one—”the best way to meet new people”—is no longer included.

Did I mention that the photo was semi-staged? Does it matter?

Harry Shunk and János Kender are not household names and not names that I would recognize, but I know the photo—the guy leaping off the rooftop above some small street in France. His leap is “only” from one story up but it looks too high for safety, his position seemingly wrong to transform into any sort of super-gymnast tumble, the image too old for Photoshop.

The man in the photo—I didn’t know this until I read Campany’s text—is the artist Yves Klein, who was a kind of nut, but not that much of a nut, not a leap-off-buildings nut. The image is Klein’s idea, the photographers hired, the image composed of two negatives made one after the other with the camera unmoving. The first negative must show the street with Klein’s friends holding a tarp for him to jump into as he leaps into space, a second negative showing the empty street. Blend the two together, hiding the landing pad, and it looks like Klein will surely crash into the pavement. My photographer’s eye regrets the lack of visual separation of Klein’s body against the tree behind—it probably looked fine to the eye in color with the tree green and Klein in black—but otherwise this image is a treat.

On Photographs is just getting warmed up. The next page has one of Muybridge’s later motion studies. A horse, you ask? A naked man, running? No, no. What we have here is a small bomb exploding next to a gathering of chickens. See how they run!

Regrettably, someone at the MIT Press thought the images in the book would be best served by using a grid of large half-tone dots—you can see them clearly with the naked eye—and so the small individual images of Muybridge’s series remain indistinct and hard to read, dissolving almost completely into abstraction when magnified with a loupe. I see the smoke, I see chickens. But did Muybridge blow up a chicken? I can’t say but my god, did he?

Pages 68 and 69 offer a deep lesson to the practicing photographer. A hard lesson to learn.

Look at that contact sheet. At first, all looks normal and then it hits you—she is shooting one image of each thing. Except for the baby in the carriage, she is shooting just that one image and moves on. She doesn’t shoot different angles, she doesn’t shoot again and again trying for a variety of expressions. She doesn’t not know what she wants. This seems easy to a non-photographer but it is incredibly hard and it is a skill developed over time, usually forced upon an artist by a lack of resources, the need to carefully husband your limited film. Many young artists have never experienced such want and despite their trust funds they are the poorer for it.

At some point it will occur to you as it occurred to me: this book is fun. Flip through it at random, read it front to back (I did it both ways) and it rewards the effort.

Let’s do one more.

That’s the artist John Divola out there, running away from his camera across the desert. He set the self-timer which gave him ten seconds and just ran full out, never hoping to really escape the camera’s reach. It works on the same level as a joke, to explain it ruins it.

Sontag doesn’t joke. If there is humor in On Photography I can’t detect it. Humor is as uncool as beauty in some circles and as difficult to pull off well.

A.C. Grayling, writing about his own field of philosophy, bemoans a similar loss.

Not all of the classics of philosophy have an impenetrable veil of technicality and jargon draped over them, as is the case with too much contemporary philosophical writing, the result of the relatively recent professionalization of the subject. It was once taken for granted that educated people would be interested in philosophical ideas; the likes of Descartes, David Hume, and John Stuart Mill accordingly wrote for everyone and not just for trained votaries of a profession.

It’s the same all over and really just a matter of following the money. To survive today as a photography scholar you need to be at a scholarly institution, to be at a scholarly institution you need to have something to teach (or to exhibit) that stands up to comparison with the curriculums offered by the departments of science and mathematics and the better social sciences. That veil of “technicality and jargon” is a strategy, not an accident. Sontag wrote On Photography at an early stage of this process of professionalization, already bereft of brightness.

Campany is more playful than that. There’s a photograph of Walter Benjamin in the book, taken by Germaine Krull, where lost in deep thought Benjamin has his hand stroking his chin, his eyes unfocused, gazing downward, no doubt contemplating the demise of the world’s capitalistic systems. Or is he?

In this early portrait, Benjamin is thinking. Or he acts as if he is thinking. Or he is thinking that he is thinking. Or maybe we think that, because he is such a serious thinker, he must be thinking.

I’m getting a little dizzy in a good way. Benjamin, like Sontag, seems to have intentionally crafted a public persona, a sort of brand or myth-building, separate from whatever real person was more revealed in private. A portrait like this can go a long way toward creating and maintaining that public persona. Here’s one of Sontag’s efforts—with exactly the same purpose.

Sontag writes about photography but it’s a photography different in important ways from what I call photography. She speaks of it in a different language or at least a different dialect. And, of course, it is. Everyone has their own individual language, every English speaker’s language slightly different from that used by every other English speaker. Big differences, small differences, the languages are, as a whole, different.

I feel that difference acutely when I read Sontag but the gulf between my language and Campany’s isn’t as great—and I suspect the reason is photography itself. Unlike Sontag, Campany is also an artist, working mostly with found photographs, it seems. Creating work rather than analyzing it crosses the ornithologist/bird divide, allows one to see deeper into what photographers actually do and why they do it. Szarkowski was a photographer and that should come as no surprise, his every essay in Looking at Photographs demonstrating his comfort with the medium, his closeness to it.

There’s an old study in economics that looked at student beliefs before and after training in economics. With training, students felt that humans behaved in an economically rational way, the way human behavior is often mathematically modeled in the field of economics—which is to say they believed that maximizing one’s self-interest best benefits society. Those without that training, poor souls, had a belief system where self-interest was not the central tenet of their existence.

I observe the same thing with art and photography. Students who buy Sontag’s On Photography as a textbook in their formative years see photography in a different way from those who don’t. Campany’s On Photographs, though not didactic, is aimed at that same group of students, offering them a chance to see what they have been taught applied to dozens of real photographs.

But On Photographs works for those who didn’t read Sontag as an undergraduate. For us, Campany offers a guided tour of a set of photographs that he finds interesting. Turn to any page and you’ll want to stop to look, to read, if for no other reason than to see what it is that is so interesting.

On Photographs isn’t a replacement for Looking At Photographs and I don’t think it is meant to be. The audience for Campany’s book is narrower, one already comfortable and indeed favorably disposed to the Sontags and the Benjamins and the Bartheses and it all. At the same time, the audience is broader than just that—I just flipped through the book, stopping at a dozen or more of the images and reread the texts without a Sontag, Benjamin, or Barthes in sight. Campany is trying for a middle ground, even a higher ground, aiming to write for everyone and not just for trained votaries of a profession.

If you think this book will make you a better photographer you’ll be disappointed. No one thinks about this stuff when planning or making images (exception: See economic study, above).

But you do want this book.

John Ruskin, the famed English art critic of the 1800s, makes a convincing case that drawing should be a skill mastered by every educated person. In that same way that nowadays we think that everyone should learn mathematics and everyone should learn a bit of science—not because you expect students to become PhD mathematicians or research scientists but because those students will then have a deeper understanding of how things work—Ruskin wanted to people to learn to draw, not to become artists but in order to see and experience the everyday world more vividly.

Teach them to draw, you teach them to see.

On Photographs, like Looking at Photographs, does much the same, escorting the reader from image to image, helping them to take the time to look at the picture, to ponder upon it, to notice it. Not every reader will become a scholar, not every reader will become an artist, but every reader should close the book, at its end, ready to start looking at photographs, to start looking in photographs, which might be a fine title for Campany’s next book.

Pingback: Listicle: Top 7 College Photo Textbooks - A Bigger Camera

Thanks. Interesting view.

Such a well-written review, thank you. Serious-minded, lay-readable, just great stuff all-around. Definitely buying the book.

Pingback: Book Review: Photographers Looking at Photographs-and Writing About Them - A Bigger Camera