Brodovitch’s issue of Exakta Magazine in 1952 has only about a third as many photographs as the subsequent one, and I know none of the photographers. Thus, Google.

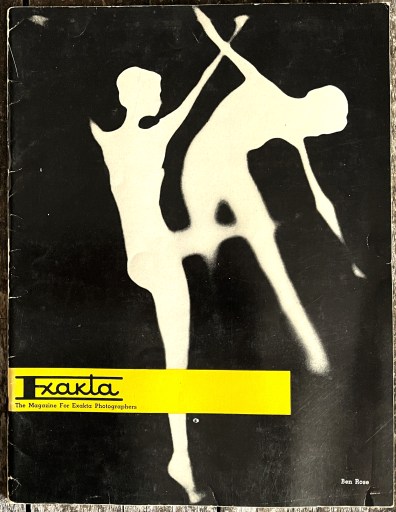

A first glance you might think the cover is a high-contrast reversal of one of Brodovitch’s own photographs of the ballet, his famous book, titled simply Ballet, published seven years earlier. But it is not his—the name Ben Rose is printed in small print at the lower right of the cover.

So, who was Ben Rose? Rose was a student of Brodovich’s and a close associate throughout his life. The cover image is not of ballerinas but people exercising—the original, unreversed image had appeared in Harper’s Bazaar, the magazine where Brodovitch was creative director, two years earlier. The article the original photo accompanied is “The 9-Minute Wonder Exercises.”

Opening the magazine we come to the fly photograph. It’s an impressive photo, made even more impressive when you read the text and learn that the fly is in-flight at the time of the exposure. The photographer and author of the text is Bert Leidmann-Warlies but Google doesn’t have much to offer on him.

I think this fate has overcome many people. They are pre-Internet and have simply vanished in all but the memory of their children.

Skipping over the Exakta camera article where no author is given we move on to the “Chimneys of the City” article and the stark images of smokestacks in Greenwich Village by Diane and Ray Witlin. They were also associated with Brodovitch—when you got Brodovitch you got his people, too. These images (or ones from the same series) were printed in Life Magazine the prior year, the captions both here and in Life playing with the shapes, wondering at the chimneys’ resemblance to parents with strollers, clowns, and cows. There’s an interview with his second wife after his death and a story of an exhibition of his work in Maine. There’s a paid obit in the New York Times as well. I couldn’t find anything sure about Diane.

“Lighting Scientific Pictures” is on microscope photography by scientist Margaret Markham. She is listed as a pioneer in general advances in medical photography, the 1951 article citing yearly advances from 1932 to 1951 with Markham’s notation in 1950 for “fundus photography” by which they appear to mean photography of the back of the eye. The year after (but the year before the publication in Exakta Magazine) she published “Modifications of the Zeiss-Nordenson Retinal Camera” in an American Medical Association journal (behind a subscription paywall like so many research papers funded with federal dollars). I can find nothing else on or by her.

Robert W. Mitchell wasn’t a photographer at all, and wasn’t an architect in the normal sense of the word, despite the publication here of his photographs of architectural models. During World War II he was trained in both American and British schools for model builders. What sort of models? Models of cities and factories, German ones, so that bomber crews could train, could peer through their bombsights to visually locate their target on the acutely reproduced models before flying over the real city.

Back in Boston after the war he started a business—Mitchell’s Models—which made models for architects to show their clients, back when building a model first was an unusual thing to do.

The next page of B-52 bombers—I’m not sure if Brodovitch intended this segue from bombsight model to bomber—seems to be a graphic work by Brodovitrch himself, using an image of a single bomber shot by Glenn Jones, the head of Boeing’s Engineering Photographic Unit. Brodovitch (or someone who is of the same mindset as Brodovitch) repeated the image of the airplane and its contrails and then reversed the tones.

No picture here better captures Brodovitch’s approach to photography than this one. The photographer’s negative was not some scared score to be played in some quasi-religious darkroom ceremony, nor was it all about subject matter and nothing about art. It was just one more raw material, open to manipulation in the service of the final feeling of the work, which is to say, the page. I suspect that neither Ben Rose (the cover image) nor Glenn Jones were queried as to whether they approved the changes. Brodovitch just made them.

George Berkowitz is listed as the editor of Exakta Magazine and an article by Berkowitz seems to be in every issue. It’s the same with Wolf Wirgin. Berkowitz appears in Google as later authoring books about Exakta cameras. Wirgin, ends up in a legal case involving the making of Exakta cameras without the rights to the name, and in 1954 started producing a line of cameras called Edixa, popular in Germany, still valuable on the used market. A person of the same name appears at about the same time as an expert on coins and coin collecting. It really has to be him, right?

“Variations On A Theme” serves two purposes. It brings in another photographer from Brodovitch’s circle, Lillian Bassman and it also serves as a little T&A, for which photo magazines (and how-to books) of the time usually reserved at least one photo or short article.

Bassman is the one photographer here that I had heard of but, since I don’t follow fashion photography much, I could not recall any of her work. A book of her work was published in 1997 by Little, Brown, so she is not forgotten. And note that she is the third woman photographer printed in this issue—that’s a high number for 1952. The next issue will have almost three times as many images as this one, half again more photographers, and only a single image made by a woman (with the improbable name for a photographer of Gita Lenz).

The final authored work is on Moon photography, by Sidney Freidin. I could find nothing on Freidin, alas, which ends things rather abruptly.

The magazine as a whole has an unusual cast of characters. We have Brodovitch’s circle supplying the core imagery, supplemented by three sets of scientific images, on flies, microscopic photographs, and astrophotography. There are no landscapes here, no portraits, unless you count the odd soaped-devil self-portrait image submitted by a reader. In fact, many of the photographs aren’t photographs in the normal sense of our expectations. The cover is a nearly pure black and white image, more graphic than photographic. The chimneys could be cardboard cutouts, there are no grays in those. The microscope images are semi-abstractions, the white bombers similarly abstracted as they fly through their black sky.

Brodovitch is well known, even revered by some, in graphic design circles. But he is much less known in photography circles. Despite Ballet his name just doesn’t come up outside of New York Fashion photography and only then because of his association with famous photographers of the day (often they were his students).

I wonder what photographers back in 1952 thought when they got their copy of Exakta Magazine, issue one? This issue didn’t want for technical information—every article covered the gear and the methods of making the images while the interleaved article-ads dove deep into the details of the Exakta cameras and lenses.

But still…did they wonder what happened to all of the photographs of children and railroads and automobiles and pets?